Chapter 4: Running Aground

|

| Seen on a pickup truck in McClellanville, SC (MM 430). |

Surviving Thriving on the ICW

4. How to Avoid Running Aground in the ICW (and when you can't avoid it, how to run aground with style)

There are many infamous spots with “skinny water” on the ICW. Just mentioning places like Jekyll Creek, Little Mud River, Hell Gate, and Isle of Palms strikes fear in the hearts of many cruisers. Fear not. You will probably run aground and it (probably) won’t be the end of your world.

First, let's describe some of the important Aids to navigation that you will encounter on the ICW and discuss the navigational information that they convey to you. "Aid to navigation" (or "ATON" for short) is a catch-all phrase for any device placed along the waterway that is intended to help mariners determine their location or their heading, relative to the established navigation channel. Think of ATONs as being the street signs and lane lines of the waterway. On land, some street signs tell you where you are ("This is the corner of Fifth Avenue and Broadway.") and some direct you to where you want to go ("Turn here for Brooklyn."). Lane lines show you the traffic patterns and where it is safe to drive your car. ATONs serve the same purposes. ATONs include items such as channel markers, lights and range markers. Channel markers are also known as lateral marks because they indicate the outer edges of the channel. There are two basic types of channel markers on the ICW: daymarks (also called beacons) and buoys. Daymarks consist of pilings driven into the seabed that have either triangular red or square green sign boards mounted on their tops. The green and red floating buoys come in a variety of shapes and sizes and are anchored in place. A buoy's distinctive shape indicates its purpose. Daymarks and buoys that mark a channel are red and/or green in color. Daymarks are more common on the ICW than are buoys. Buoys tend to be found near the inlets, especially those that are major ship channels. The buoys in the ship channels and near the ocean are usually larger than those found in shallower, more protected waters. The shapes of the small red and green buoys differ from each other; the greens are flat-topped cylinders called "cans" and the reds are cylinders that have cone-shaped tops and they're called "nuns" (their pointed tops are said to resemble a nun's habit). These lateral daymarks and buoys are numbered. Reds are even numbers, greens are odd. The numbers help you to determine your exact location. If you are beside red buoy #2 (abbreviated R2), you know exactly where you are on your chart. On the ICW, channel marker numbers increase as you head clockwise (i.e., as you head south along the Atlantic Coast). Because there are thousands of channel markers on the ICW and it would become too difficult to read numbers with 4 or 5 digits, the numbers periodically reset to 1.

ICW channel markers don't follow the typical "red right return" convention (i.e., When returning to port from the sea, keep the red markers on your starboard, or right, side.). The ICW doesn't lead from the ocean to an inland port. Instead, it parallels the coastline. For ICW markers, the reds are on the side of the channel that is closest to the mainland and the greens are on the side closest to the ocean. Thus, the convention is "red right clockwise." That is, as you move clockwise around the coast from Virginia to Texas, keep the reds on your starboard side. To determine which side to pass a marker on, you need to know if that marker is for the ICW or for another channel. ICW markers can be identified by the gold triangles and squares on them. Usually, the red markers have gold triangles and the green markers have gold squares. However, where the ICW crosses another channel, one marker can serve to mark both channels. Occasionally, one marker can serve as a green for one channel and a red for the other. For example, there may be a green beacon that has a gold triangle on it. This means that if you were inbound from the ocean and saw this marker, you would treat it as a green. However, if you were transiting the ICW and saw this same marker, you would treat it as a red, even though its main color is green. That gold triangle means it is a red marker for the purposes of the ICW. Intersections are often indicated by channel markers that are both red and green. To stay in the ICW, look for the gold shape to tell whether you should treat such marks as red (gold triangle) or green (gold square).

The other types of ATONs on the ICW include:

- "Isolated Hazard" Buoys are black and red buoys that can be passed on any side. But remember to keep your distance; there is a hazard to navigation lurking just beneath the surface near that marker.

- Dayboards say "You are here." They are diamond-shaped boards on which there are two colored diamonds, one on top of the other with their points touching. These are usually found around the busy commercial ports.

- Special Marks are yellow daymarks or buoys that have no "lateral significance." That is, they don't tell you where you are relative to the channel. These are often used to mark the boundaries of anchorages, fishing grounds, or dredge spoil disposal areas.

- Range markers help you to visually determine whether you are in the middle of the channel. Range markers come in pairs, both members of which have identically-colored sign boards with a vertical stripe down their centers. The two markers of a pair differ in height, and when the sign boards from the two markers are aligned vertically, you are in the center of the channel. These used to be very common on the ICW. Now you only find them near the large shipping ports.

- Information/Regulatory markers are white buoys or daymarks with orange symbols and black writing. They are used to indicate special areas such as no wake zones, speed zones, boat exclusion zones, etc.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, you shouldn’t focus entirely on your chart plotter. You need to be looking out at the water. You should always be looking for the channel markers that appear on the chart to make sure they are located where expected. And you should look at least two markers ahead so you can visualize your path, whether you are hand-steering or using your autopilot.

| M/V American Independence |

| The M/V American Independence, one of the cruise ships that travels up and down the ICW, is 226 feet long with a beam of 39 feet. And, as you can see from the close-up photo, it draws almost 8 feet. This ship and others like it navigate the ICW from North Florida to Chesapeake Bay, much of its traveling is done at night. If this ship can navigate the ICW, your 6-foot draft won’t be a problem. |

The most basic thing that you need to know to avoid grounding is how to interpret the depth soundings on navigation charts. It doesn’t matter if you are using paper charts, raster charts, vector electronic navigation charts (ENCs), Navionics Sonar Charts, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' depth surveys in Aqua Map, or any other form of navigation chart; they all express depth soundings relative to mean lower low water (MLLW; see Chapter 2). If your chart shows that there is 6 feet of water at a specific location, it means that there is 6 feet of water there during the average lower low tide. Because it is an average of the lower low tides from each day, the actual depth at that location should be somewhat greater than 6 feet most of the time (assuming the sounding is accurate and there hasn’t been any shoaling in the area since the sounding was taken). However, there will be times when the depth is less than the charted 6-foot depth; specifically during low tides that are lower than the average lower low tide (i.e., during the spring tides that take place around the full and new moons). To calculate the actual depth at high tide or low tide at a specific location, look at the tide predictions for your area, which will show both the times of the tides and the tidal heights, or offsets from MLLW. Add the offset shown on the tide chart to the sounding on the navigation chart. During high tide, the offset number will always be positive and relatively large. During low tide, the number will be smaller and usually positive. But sometimes it will be a negative number. These “negative tides” are when the water will be extra low. So in this example, the low tide at 4:56 AM was 0.47 feet below MLLW and the high tide at 10:59 AM was 3.16 feet above MLLW. This means that the actual depth at the location where your navigation chart shows a depth of 6 feet was 5.53 feet (6.0 - 0.47ft) at low tide and 9.16 feet (6.0 + 3.16 ft) at high tide.

| Tide charts provide two important pieces of information: the time of each tide and the height of the water above or below (negative numbers) the level at mean lower low water (MLLW). |

At most of the notoriously shallow spots on the ICW, the main problem is not the depth, per se. Instead, it’s the narrow width of the channel, coupled with a cross-current and/or crossing wind. You often hear people say “I was in the center of the channel when I ran aground.” Nine times out of 10, they were out of the channel and didn’t realize it. Remember that your bow isn’t necessarily pointing toward the direction in which you are headed. When you pass an ocean inlet or an intersecting marsh creek, expect sudden changes in the direction and speed of the current, which will probably push you sideways. If you are slow to recognize this situation, you could go aground or run into an obstacle. Anticipate these changes in current at intersections and be ready to compensate by steering into the current. Stay current on the current. And don’t just look ahead; make sure you also look behind. You may think you are safely within the channel because your bow is pointed toward the next pair of red and green markers when all of a sudden, you feel that dreaded “thud.” You then look around to try to figure out what happened, and you may notice that the last few markers you passed are no longer directly behind you but rather they are all off to one side. A cross-current set you sideways. This can happen in seconds. The best way to avoid this fate is to periodically glance behind you to make sure the markers you just passed are still where you expect them to be. Visually line up the markers ahead of you with those behind you to make sure you are still in the channel.

If you look closely, you can usually see signs of where the current changes (different rippling pattern of the water, a line of foam, a calm slick, or a distinct change in water color). Before you cross into a new water mass that is moving in a different direction from the water mass that you are currently in, you can alter your heading to make sure you stay on a safe track. And although your autopilot is really sophisticated, it cannot look ahead and anticipate rapid changes in the speed or direction of the current, and it can’t adjust your engine speed.

| Jekyll Creek, Georgia: an example of an infamous spot for groundings, where the real problem is width, not depth. This image of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers depth survey is zoomed in as far as possible in Aqua Map. You can see the measurement of the width of the channel, where the water exceeds 5 feet, is only 0.03 nautical miles (= 180 ft). The portion of the channel that is greater than 7 feet in depth is one-third as wide, or 60 ft. If you want to stay within that center stripe of orange that represents water that is at least 7 feet deep, you have to stay within that 60-foot swath. With two-way traffic, you actually only have about 30 feet. If your boat has a 14-foot beam, that means you have about 8 feet of clearance on either side. That doesn’t leave much room for error. To complicate matters, there is a marsh creek that intersects the ICW just above the top left corner of this image. The cross-current coming from that tributary creek doesn’t have to set your boat sideways very far to cause a problem. To make it easier to transit this area, use Aqua Map (Master version) with the USACE depth survey enabled and the Bob423 ICW track (see Chapter 8). Zoom in on Aqua Map as far as it will go and pay attention to the intersecting creeks and the movement of the water. |

Depending on the vessel traffic conditions and your ability to see any traffic that may be coming around a corner, it’s good practice to keep to the up-current or windward side of the channel. Old salts refer to this practice as “Putting Money in the Bank.” Doing this keeps you further away from danger when your boat is being pushed sideways or in the event that you experience mechanical failures. Staying up-current or up-wind gives you more time to recognize and react to the problem before it’s too late. Even if you lose propulsion, putting money in the bank will give you a fighting chance to get your sails set or your anchor down before you go aground. But remember Rule 9 of Inland Navigation Rules; vessels should keep to the right in a restricted channel when there is traffic coming in the opposite direction and around blind corners.

| A straight, narrow section of the Gulf ICW, just north of Sarasota Bay, FL. The yellow line represents a vessel’s track. This pattern, where the boat has turned slightly to starboard after each red marker then corrected is a clear sign that the boat was being pushed sideways by the wind or current. In this case, a strong wind was blowing from left-to-right across the channel. Even though its bow was pointed at the next set of markers, the boat was moving a bit sideways. This can happen without the operator even realizing it. This problem can be detected either by glancing back at the markers that you have just passed or by running aground (not the preferred method). By glancing backwards, you will quickly notice if the boat is straying out of the channel because instead of being directly behind you, the markers that you just passed will be off your stern quarter. |

An explanation of what is happening in the previous figure. A strong breeze on the port side is pushing the boat toward starboard. Even though the bow is pointed up the channel, the boat’s actual direction of travel is carrying it outside the channel. |

When you run aground, it shouldn’t ever come as a complete surprise. You must be aware of your surroundings, know where the shallow, tricky spots are, and slow down when the water is getting skinny or if you are unsure where the channel goes. The slower your speed, the less likely it is that you will damage anything. If you run aground at a speed higher than idle, then you probably weren’t paying attention. Remember that it’s your speed over ground that really matters when you hit something that is stationary, such as the bottom. If your engine is pushing you through the water at 5 knots and a fair tide is adding another 2 knots, then you’re going to hit with a lot of force and risk causing serious damage.

The deepest water is not always in the center of the channel. When going around a curve, the water toward the inside of the curve will tend to be shallower than that on the outside of the curve. As the water flows around a curve, the water along the outside of the curve moves faster than that on the inside. The faster moving water picks up sediment from the bottom and carries it away. In contrast, the slower moving water drops sediment, which is deposited on the bottom. Take the corners wide to find the deepest water (but remember to keep clear of oncoming traffic; Inland Navigation Rule 9). In particular, don't try to cut a straight line from marker to marker on the inside of a corner. The curved edge of a shoal on the inside of a bend in the channel can often stick out further toward the channel than a straight line drawn between two markers on the inside edge of that channel. Many boats run aground because they turn too early or cut the corner too tight. Water depth in straight-aways tends to be shallower than the depth in the corners or bends. And there are often shallow, complex shoals where creeks and inlets intersect with the ICW.

| The ICW between Charleston and McClellanville, SC. Note the shallow water (red) on the inside of the curve to the northwest of marker R86. By taking a straight line between R84 and R86, there is a good chance that you would go aground. Don’t cut the corners too closely. It is common to have shoaling on the insides of the curves and deeper water toward the outside. (Aqua Map with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' depth surveys displayed in the Waterway Guide Explorer, https://www.waterwayguide.com/explorer?latitude=32.904017264651586&longitude=-79.67491203392125 &zoom=15.784371982643629&mode=anchorage-freeDock.) |

| The ICW at Isle of Palms, SC. If you attempted to cut straight from R122 to R126, you would almost certainly go aground. Even if you “pinballed” diagonally across the channel from G123 to R126, you’d still probably go aground. Stay wide on the corners. (Aqua Map with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers depth surveys displayed in the Waterway Guide Explorer, https://www.waterwayguide.com/explorer?latitude=32.76657153749491&longitude=-79.85535728484771& zoom=16.016963575390108&mode=anchorage-freeDock) |

Daymarks are oriented such that you can only see their colored sign boards when you are in the channel. If you stray outside of the channel, you probably won’t be able to clearly see the nearest daymarks. At this point, any marker that you can see is likely to be much further away, and there is a good chance that there is shallow water between your position and that marker. If you go astray, the best thing to do is to turn around and retrace your route until you are back in the channel. Follow your breadcrumbs to find your way out of the woods!

Green channel markers are often camouflaged. Green buoys and daymarks are difficult to distinguish against a background of green trees or marsh grass. To help find green daymarks that are in front of vegetation, look for the bottom portion of the piling itself, below the horizon line of the water. It’s usually easier to pick out the dark-colored piling in front of a background of water than it is to see the green marker itself in front of a background of green vegetation. Binoculars are also useful for finding these marks; keep a pair near the helm.

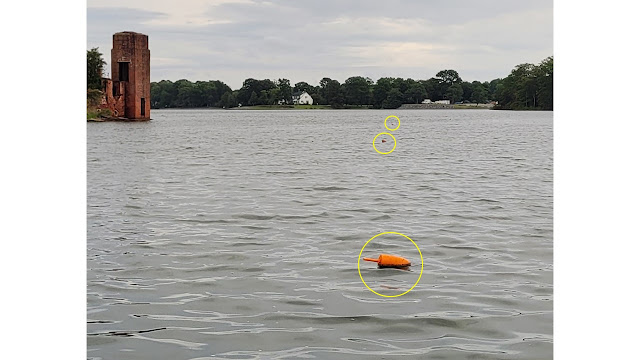

Beware of the nuns and cans. Unlike in the ocean and in deepwater commercial ports, where the channel markers are large floating steel buoys, most of the channel markers on the inland waters are daymarks. However, every once in a while, you will see small red “nun” and green “can” buoys on the ICW. Be extra cautious when you come across these nuns and cans. Floating navigation buoys on the ICW are often indicative of areas that are shallow and “shifty.” Where the channel is actively shoaling, the aids to navigation have to be moved frequently. It’s easier for the Coast Guard to reposition small floating buoys than it is to extract a piling that has been driven into the seabed and drive it back in at another location.

Figure: photo of small buoys & day marks (talk about gold triangles & squares)

In the previous chapter, we discussed how crab pot buoys can be useful for gauging the water’s motion. Here again, crab pots are your friends. Crabbers generally set their gear on the outskirts of the channel, along the edges of the shoals. Their practice of setting the pots in lines that follow the bottom contours can help you identify where the shallow water is and where the edge of the channel is. There are exceptions to this, but crab pots can be used as another type of navigational aid. If you are dodging and weaving through a lot of crab pots, you are probably not where you’re supposed to be. The one exception to all of this is in Albemarle Sound, near the confluence of the Alligator River (MM 81). It's open water at that point, and there is no well-defined channel, so the pots are set all over the place.

Because the current is usually quite sluggish near the tidal convergence zones (behind the centers of barrier islands, roughly halfway between two adjacent inlets), particles of sediment that are being carried by the water tend to sink to the bottom at these locations, causing shoaling. It turns out that many of the notoriously shallow sections that are subject to shoaling are at the tidal convergence zones (Jekyll Creek and Little Mud River in Georgia, for example). The good news is that these shallow areas generally have gentle currents, they are sheltered from large waves, and the bottom sediments tend to be very soft and gooey. So if you’re going to run aground anywhere, it might as well be at one of these shallow tidal convergence zones. An inlet, on the other hand, is a much more dangerous place to run aground. Inlets, like St. Andrews Inlet south of Jekyll Island, have swift tidal currents, they are exposed to the open ocean so they have much more wave action, the bottom sediments are mostly sand (which is much harder than mud), the bottom topography tends to be complex and changes rapidly (across space and time), and sometimes have rock jetties or riprap. The consequences of running aground in an inlet are far greater than doing so well inside an estuary. Remember: It’s the inlets you need to worry about! (See Chapter 6 for more about inlets.)

As described in Chapter 2, it is helpful to use some ecological knowledge to determine whether you are going to have to go through some skinny water. In the tidal salt marshes between Swansboro, NC, and St. Augustine, FL, remember to look for the mud flats, living oyster reefs, marsh turf, and Spartina grass to gauge the current state of the tide (see Chapter 2). In the non-tidal areas, watch for the dark-colored algae growing on pilings and bridge clearance (“tide”) boards. Seeing the mud flats (tidal) or algae (non-tidal) tells you that the water is low.

The water on the ICW is definitely not crystal clear, by any means. It is dark and cloudy, especially in South Carolina and Georgia. It’s not that it’s dirty or polluted. The water is this way because of tannins (naturally occurring organic molecules derived from plants; the same thing that gives color to tea and red wine), sediment particles picked up by the moving water, and microscopic algae. It’s not important to know what causes the water’s cloudiness, but it is important to know that it prevents you from seeing the shallow spots (unless it’s really shallow and by then it’s way too late). You’ll be in ankle-deep water before you see the bottom. Although you can’t see the shallows, you can look for clues that will help you identify shoals and the boundaries between two water masses moving at different speeds. You’ll often notice where the “texture” of the water’s surface changes abruptly. In one area, there may be ripples or wavelets and in another, the water may be perfectly smooth. And you may notice that the boundary between these two areas generally corresponds with the depth contours on your chart plotter. You may also notice foam or dead marsh grass floating in a line along these boundaries. What you are seeing are two different water masses that are moving at slightly different speeds. Water in the deep channel moves more freely, whereas water moving over the shallows slows due to friction. If you are already in the deep channel, try to avoid straying across these boundaries, especially if they appear to be toward the edge of the channel. If the water is getting shallow and you see one of these boundaries in the direction of the channel’s center, go ahead and cross it.

To get some hints about the depth and contour of the bottom, look at the slope of the nearest shoreline. If there's a bluff that plunges straight down to the water, the deep water MAY extend close in, close to shore. If the land slopes very gently down to a broad beach and or an exposed mudflat, then the shallows probably extend pretty far from shore. Coves and embayments tend to have deeper water close to shore, whereas a point that juts out into the water usually has shallows that extend far out from it. Give a wide berth to points of land that stick out into the water.

For the most part, as long as you stay within the marked channel, you won't have any problems. You can follow the channel markers visually, but navigation electronics make that job much easier. We highly recommend using the "Holy Trinity" of Aqua Map running Bob423's ICW tracks and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' (USACE) depth overlay. The Bob423 ICW tracks and USACE depth overlay are the gold standard for ICW navigation. Bob423's tracks can be displayed by any charting app that allows you to import and display track files. However, Aqua Maps is the only charting app that allows you to display the USACE depth overlay. Regardless of which navigation chart system you use, the chart display should be zoomed in as far as possible. Zooming in does two things: 1) it shows the greatest amount of detail on your chart and 2) helps show precisely where your boat is located on that chart. If you zoom out too far, it may look like your boat is in the center of the channel when it actually isn't. (See Chapter 8 for more on this topic.)

For real-time information on conditions along the ICW, including on all of the shallowest trouble spots, we recommend joining and following the ICW Cruising Guide by Bob423 Facebook group. This is a forum for ICW cruisers, created and maintained by ICW cruisers. We also recommend the ICW Cruising Guide by Bob423. This is a printed guide that covers a lot more topics than you find in a traditional cruising guide. It includes information on the safest routes, how to avoid the common shallow trouble spots, hazards to navigation, and the skills needed to navigate the ICW.

| Navigating the inland waters of the Southeast can be a game of inches, both vertically and horizontally. Running aground on the upper half of a falling tide means you're going to be there for a while. |

If you know you are approaching shallow water, slow down! Remember that coasting in neutral is allowed, especially if you have a power boat with an unprotected prop(s). The chances of that expensive prop being damaged in a grounding are far higher if the engine is in gear and the prop is spinning at several hundred RPMs. If you were moving slowly, then you will probably be able to free yourself pretty easily. See the box below for a few maneuvers to help free yourself from a grounding.

_______________________

Box

- If your engine is still in gear when you feel contact with the bottom, take the engine(s) out of gear immediately.

- Back off gently in reverse gear. Only try this if you’re sure that the prop isn’t in contact with the bottom. If you have a twin engine boat, try to keep one engine in neutral until you are free. That way if you damage a prop on the bottom, you’ll still have propulsion from the other engine.

- Set a kedge anchor (use your dinghy to set an anchor out in the deep water and then use your windlass or a winch to help pull you off.)

- Wait for the tide to come in (hopefully you haven’t run aground at high tide). It helps to set a kedge to prevent the incoming tidal current and wind from pushing you further up onto the shoal.

- If you have a monohull boat, lean it over by redistributing weight. You can pump fuel or water from one tank to another, move heavy items, fill buckets with seawater, and have the crew sit along the outboard edge of the boat. If you have a sailboat, you can hang weight on the end of your boom (e.g., a bucket of water) and let your boom out. Don’t try leaning your boat over if you have a sailboat with a winged keel or dual rudders, if you have a powerboat with twin engines or stabilizers protruding from the hull, or if you have a catamaran of any kind.

- If you have a monohull sailboat, you may be able to use the sails to both lean the boat over and to power it off the shoal. The first thing you have to do is get the boat turned back toward deep water. Depending on the wind speed and direction, you may be able to use the mainsail and genoa to gybe it around or you may be able to backwind the genoa to get the boat to tack through the wind. Other options include using a dinghy or a kedge to pivot the boat before setting sail.

- If you have a monohull sailboat and a good dinghy, you can use a halyard (perhaps with another long line tied to the end) to lean the boat over. The halyard runs from the dinghy to the top of the mast, through the sheave, and is tied off at the base of the mast. The dinghy pulls on the halyard sideways (in a direction that is perpendicular to the hull of the boat). The dinghy IS NOT attempting to drag the boat off of the shoal by its mast; this would be a good way to damage the rig. It is simply leaning the boat over. Once it is leaning, the boat’s engine should be used to power off of the shoal (or a third vessel can tow the grounded vessel off). The longer the halyard, the easier it will be for the dinghy to get the boat to heel over. If the dinghy isn’t powerful or heavy enough to get the boat to heel over, you can set a kedge and tie the halyard to the anchor rode. Taking up on the halyard should heel the boat. You will need as much scope as possible.

_______________________

Conclusion

“If you ain’t been aground, you ain’t been around!” It’s cliche but true. Spend enough time cruising in shallow water, and you’ll eventually go aground. Most likely, this experience will cost you nothing more than a few hours of lost time (and maybe a bruised ego). Thankfully, the bottom throughout most of the ICW is pretty soft. The “pluff mud” in South Carolina and Georgia is hardly any firmer than the water, and you can often just go right through it. The further you are away from an inlet, the softer the mud will be. Close to the inlets, the bottom is mostly sand, which is much more firm. If you do run aground and can’t free yourself immediately, then settle in with something good to read. Or break out the plastic scraper and clean your bottom while you’ve got the chance. Just watch out for that pluff mud!

|

| The MFD (multifunction display) on our sailboat, Fulmar. This photo was taken in Jekyll Creek at dead low tide on a negative tide. Note the depth (-0.5 ft), which is calibrated to the bottom of our keel. Our boat draws 6 feet and there was only 5.5 feet of water. Now note the speed over ground (4.5 knots). Because we were still in the channel, where the mud is the softest, we never felt the boat bump and the speed never slowed. The mud in the channel is not much firmer than water. Outside of the channel, in the shallower water, the mud becomes more solid. |

To Learn More

- ICW Cruising Guide by Bob423: A printed cruising guide that goes beyond the scope of traditional cruising guides. Includes information on the safest routes, how to avoid the common shallow trouble spots, hazards to navigation, and skills needed to navigate the ICW.

- ICW Cruising Guide by Bob423 Facebook Group: A great online community of ICW cruisers.

Tools

- NOAA Tides & Currents Predictions: Predictions for the future.

- NOAA Water Levels: Actual water levels measured at tide gauges for the present and past.

- Bob423 ICW Tracks & Routes: Downloadable GPX files that you can put on your chart plotter, or any digital device that runs Aqua Map or Navionics. The track for the entire AICW, from Norfolk to Miami, is covered in four separate track files. These tracks show the best deep water route through the AICW, and are updated frequently, as needed. As of May 2024, the most problematic stretch of the entire AICW is near Isles of Palms, SC (MM ~460.5), where the depth at MLLW is now less than 4 feet. There is a track for a detour around this trouble spot. This spot is not likely to be dredged until at least 2025, so we'll be living with it for a while. The file with the 18 side tracks is also helpful for getting into some popular anchorages and marinas. For Garmin chart plotters, you also need to use the Track Splitter.

- Aqua Map: Navigation app with many useful features and capabilities for ICW cruising. The "Master" version gives the user access to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers depth surveys, Bob423 ICW tracks, and data on tides and currents.

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Tips & Tricks

- Chapter 2: Water Levels

- Chapter 3: Avoiding Obstacles

- Chapter 4: Running Aground

- Chapter 5: Bridges

- Chapter 6: Inlets

- Chapter 7: Docking, Anchoring & Mooring

- Chapter 8: Navigation Electronics

- Chapter 9: Weather Basics

- Chapter 10: Typical Weather

- Chapter 11: Environmental Stewardship

- Chapter 12: The Perfect Boat

- Chapter 13: Maintenance

- Chapter 14: Conclusion

- About the Authors